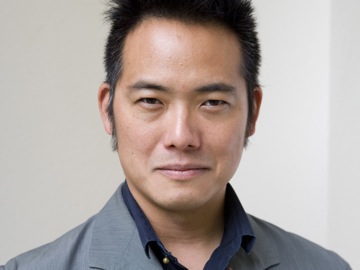

Give composer Ken Ueno five minutes and he can find a way to link Buddhism, Mongolian throat singing and Robert Kennedy. Give him another five and he’ll weave in molecular gastronomy and gang violence. Next he’ll add James Joyce and Ovid, the Roman writer. If his life takes this form of polyglottal all-inclusiveness, then so does his art. If nothing is out of bounds, then everything is drawn into his art.

What’s fascinating is that Ueno’s theme, when he comes to Providence later this month, is meditation. Traditionally meditation acknowledges our flurry of stimulating ideas, desires, ambitions, and asks us to narrow down, focus and ultimately empty the mind to achieve a state of unity and release. With Ueno’s energy, it might be challenging for him to calm his creative system. But the other part of the visionary meditative state is the realization that everything is connected, part of the One. And Ueno’s passion is definitely for making connections.

Ueno’s “Four Contemplations,” commissioned by Community MusicWorks and presented from March 26-29, will be total immersion into Ueno’s fascinating, floating world. The work will initially be set in the RISD Museum, where eleven classical players in Community MusicWork will perform in 30-minute segments while moving around the Asian galleries. Listeners will also be filtering in and out, music will bleed from one gallery to another. The vocals will be unlike any other: Ueno specializes in Tuvan throat singing and other radical vocal extensions. Presiding over the world of difference will be RISD Museum’s treasure the Great Buddha who, due to renovation, was absent and is now returning to presence.

Known as a cross-disciplinary composer, Ueno’s jumping off point was the Dainichi Nyorai Buddha in state of bliss. His four segments correspond with the four main dharmas of meditation: contemplation on mindfulness, body, feelings, and thoughts. While not a practicing Buddhist like his father, Ueno’s extended vocal techniques require great discipline of breathing, which easily makes the connection with meditation.

Born to Japanese parents in the US, Ueno has lived in Japan, Switzerland, Brussels, Paris, Rome and Berlin. He spent a year in Providence teaching at UMass Dartmouth and is now living in Berkeley, CA. “I’ve been in exile my whole life,” he says.

This sense of the cosmopolitan ungroundedness is part of the impetus of his cosmopolitan creation. “Sometimes I feel both Japanese and American, sometimes neither. ‘Not belonging’ is my natural state. Art has helped me create a center, an autonomous sense of self. My art practice organically floats between architecture and sound and improvisation and written music and classical, experimental noise,” he says.

During the weekend, Saturday’s All Saints concert will be an interactive event with CMW musicians and students. How will the students approach throat singing, which stems from an ancient Mongolian tradition, and his soundscapes? Ueno, who is a professor of music at UC Berkeley, dislikes talking down to people of any age, race or class. He remembers how silly adults used to speak baby talk when he perfectly understood their words. He advocates that meaning in art, when authentically created, can be understood by any audience. Feeding people sweet Hollywood melodies guarantees they will only understand sweet Hollywood melodies.

Ueno cites an experience from his younger days while teaching in a halfway house for delinquent teenagers and former gang members. While Ueno gained respect, keeping the students’ attention was a trial. His moment of revelation came unexpectedly. One day he played a recording of “Quartet for the End of Time,” a notoriously difficult chamber music piece written by Oliver Messiaen. During those 6 1/2 minutes, the students were held in rapt attention. It was the only time the class was silent. Once it ended, he told them that the music had been premiered in 1941 when Messiaen was a POW camp in Görlitz, Germany after being captured by the Nazis. The gang members had already grasped the essence of the shared experience, through their own months of incarceration. “If the music is good enough, it doesn’t matter how radical it is. It can communicate to almost anyone.”

As challenging as his music might be, Ueno is a believer in its beauty and power. “If you work from an authentic point of view of something that affects you, that honesty and earnestness will translate. I write music I think is beautiful. It is weird, sure. There are other things about sound, discovering sound, inventing technique that might be unusual. The lesson is: radical need not be uncomfortable.”

–Jill Pearlman

Jill Pearlman is a writer of fiction, poetry and journalism. Her in-progress novel, Clio’s Mobile Home, is based on her experiences as a music journalist in New York in the ’90s. Her blog about art, aesthetics and ecstasy can be found at http://jillpearlman.com.

More information and links to reservations for Four Contemplations events here.