“The Last Supper” painting by Jessica Van Daam, on loan to the Trinity Brewhouse.

CMW Fellow and violinist Luke Fatora muses upon Beethoven as a pop culture icon.

Earlier this year, an unexpected downpour of cold rain unleashed itself as I was out for a walk. Passing by the Trinity Brewhouse on Fountain Street, I took refuge inside and found myself seated near a musician-themed mural riffing on The Last Supper. I was enjoying a nearby table’s particularly slurred conversation – its contents better left unexplored here – when it took a hard turn. One of the speakers interrupted a waitress, gesturing towards the mural hanging on the wall where Ludwig van Beethoven (not to confused with Beethoven the dog but more on that later) was stoically seated next to Billie Holiday in the company of other musicians like Jimi Hendrix and John Lennon. He asked “Who’s the guy with the curly hair??”

I found myself thinking back to this experience recently at CMW’s Phase II students’ weekly dinner and discussion. The students were exploring the interdependent relationship between a piece of art and the settings that a culture places it in. Later that night I grappled with unanswerable questions as I tossed and turned. How would Beethoven have responded to someone telling him that two centuries into the future, Americans would scarf down nachos and beer under his quasi-religious image in a brewpub in Providence, RI? How about being told that Andy Warhol, an iconic 20th century American artist, would designate Beethoven as the figure from western classical music to join the likes of Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, and Chairman Mao, as portrait subjects? Finally, what would he have had to say about the movie Beethoven released in the 1990’s?? My guess is as good as anyone’s as to how Beethoven would have reacted to being told that his name would become synonymous with a Hollywood movie about the adventures of a goofy, slobbering, St. Bernard.

The composer’s canine namesake.

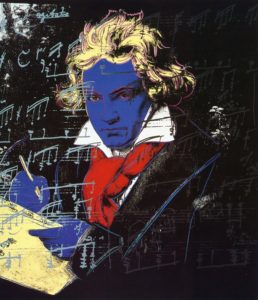

After entertaining these hypothetical reactions, we’re left with some serious questions. Why did Andy Warhol choose Beethoven over someone like Schubert or Tchaikovsky as an iconic portrait subject? Why is the comedic reboot of Lassie centered around a St. Bernard named Beethoven (the surface explanation is here) and not Schoenberg or Bach?

Warhol’s Beethoven

Beethoven was an incredibly forward thinking composer – so much so that nearly a century after he wrote his wild Grosse Fugue, composers such as Arnold Schoenberg would look back to it as a premonition of their own radical breaks with tradition. Are we to believe that Beethoven’s seat at the table of musical disciples in the Trinity Brewhouse is a result of his technical wizardry as a composer?

Another explanation lies in his easily accessible humanity. As many people know, Beethoven lost his hearing over the course of time and had a generally tough life. His struggles led him to rail against fate in his Fifth Symphony. There is hardly a more universal human experience than struggling with circumstances that are beyond our control. Beethoven’s loss of hearing is tragic and his response to continue living for the sake of creating art is certainly heroic (you can read about it in his own words in his famed Heiligenstadt Testament). This said, other composers, being human (for now…), have certainly also struggled with circumstances beyond their control.

Popular culture’s obsession with Beethoven (the composer) risks encapsulating his image in the opening bars of his 5th Symphony and “that epic part of the 9th symphony where people are singing about something in German.” Only a sliver of Beethoven’s humanity is seen when it is through this lens. Recently, I have been working through his Third op. 12 Piano and Violin sonata and have been enjoying how starkly it contrasts popular notions of what Beethoven should sound like (“bark bark bark baaaark!”). Beethoven began working on his op. 12 Piano and Violin sonatas in 1797; he was 27 years old and had been living in Vienna for 5 years. At that point, he was 5 years away from writing the Heiligenstadt Testament and presumably contemplating suicide in the face of his worsening deafness. The Heiligenstadt Testament details the agony of Beethoven’s depression but it also mentions his lifelong heightened sensitivity to “tender feelings of affection” and his general “love for man and feelings of benevolence.”

Ludwig Van Beethoven, composer and guy with the curly hair.

Beethoven’s Third Piano and Violin Sonata can be seen as stemming from these general underlying dispositions; it is brimming with a particularly sparkling and playful energy, never taking itself too seriously. The beginning and ending movements are strikingly joyful romps through E flat major. The second movement is an Adagio in C major that begins with a simple melody containing an emotional pureness that becomes transformed throughout the movement. The theme passes briefly through distant and more complicated emotional landscapes, emerging to playfully evade a committed return to its original character – one gets the sense that Beethoven is exploring what it feels like to make peace with an unattainable ideal’s imaginary nature. This is the side of Beethoven that, two centuries later, keeps me warm on a slushy February day. Beethoven’s ability to probe such an extreme range of emotion leaves me in awe of his (very human) ability to reach across time and space to connect with us and – most importantly – inspires me to stop reaching for my phone to check the latest news and reach for my violin instead.

–Luke Fatora

Please join us Thursday, February 15 at 7pm for the Sonata Series Event at RISD Museum’s Grand Gallery as Luke Fatora performs Beethoven (the composer) along with pianist Jeff Louie. The event also features violinist Jesse Holstein performing a composition by Amy Beach.