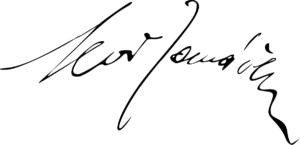

Written on Skin: Leoš Janáček’s Intimate LettersAs the Fellows Quartet prepares for this weekend’s performances, violinist David Rubin reflects on a piece by Leoš Janáček. Several months ago, I wrote for this blog about Aaron Copland’s violin sonata. My affection for that piece was uncomplicated. Every layer of meaning – biography, reception history, extramusical associations – made it richer, easier to love. Now, preparing for this weekend’s concerts at Everett Stage & Bell Street Chapel, I find myself in the opposite position. The deeper we delve into Leoš Janáček’s Intimate Letters, the more ambivalent I feel. What do you do when the circumstances surrounding a piece of music push you away, rather than draw you in? When I put bow to string and try to come to terms with the physical demands of this music, I quickly fall under its spell. Everything about it is unique. The melodies. Little cells, packed with emotional energy and ready to combine, break apart, metamorphose. They have density of meaning, like Wagnerian leitmotif, but also a plainspoken quality – they burrow into your memory and haunt for days on end. Janáček spent the better part of his career trying to enshrine the Czech language in musical prose, and you can hear that effort. It’s easy to imagine words standing behind every note. The rhythm. For most of Intimate Letters, one or more of the four players is busy shredding some frenzied, repeating pattern (in musical lingo, we call such repetition “ostinato”). Every so often, those ostinatos will converge – or clash – to dizzying effect. It’s a cliche to say that a work of small-scale chamber music is “symphonic in scope,” but in this case it rings true. The force of this combined rhythmic energy can be overwhelming. A cataclysm for four players – as written on the page, it’s almost too much to realize. Too much for a little box of wood, strung with steel or gut. The texture. People often talk about “color” in concert music, whether in reference to the harmonic language of Ravel or Debussy, full of sensory appeal, or the orchestration of Berlioz and Rimsky-Korsakov, rife with surprise. Janáček is one of the few composers who makes me feel texture just as strongly as color. A melody blurred by a rasping “ponticello” – the bow pulled against surface of the bridge – is it a memory of something precious past, or a portent of some idyllic future? A note so unexpected and poignant that you want to delay the vibrato or press the bow – things our teachers tell us not to do – because that’s what it sounds like when a singer’s voice aches, when music is spoken rather than sung. Sweetness tempered with grit. Beautiful and ugly sounds rendered in the same instant. That’s what I mean by texture. ————— But when I think about this piece, my relationship to it sours. Lately, I keep having the same experience, or variations of it. I’ll be humming one of its tunes, setting up the office for teaching… in the pause before the melody’s repeat, my brain will offer the same nagging reminder: remember what this music meant to the composer. Remember the ugliness behind those notes… ————— “Oh, it’s a work as if carved out of living flesh. I think I won’t write a more profound and truer one.”

Leoš Janáček intended this piece as a musical portrait of his decade-long, one-sided, imagined love affair with a distant woman, Kamila Stösslová. Kamila was nearly forty years younger than Janáček himself, and a complete stranger. The two met briefly in 1917, while Janáček was on vacation. She was married, and did not return his interest in the slightest… but over the next ten years he penned hundreds – hundreds! – of letters, in which he poured out his soul, proclaimed his ardor, and declared her to be his muse. When Janáček created this second string quartet – in a frenzy of creative energy, exactly ninety years ago – he was enshrining this private history in music, immortalizing it. At first, he considered treating the piece as a public declaration, by giving it an explicit title: Love Letters. A friend talked him down from the ledge – that’s how we ended up with the more elusive Intimate Letters. In contemporaneous writing to Kamila, Janáček pointed to particular scenes in the quartet as pictures of their imagined life together – one movement a depiction of the son they would have had; another a portrayal of the composer conquering all obstacles to their union (“the ground shook”). You can’t make this stuff up! Well, I guess Janáček could, but… the saying still holds!

We’ve all had unrequited loves. We’ve all preferred the contours of fantasy to the disappointments of everyday life. But to invest so much of your life’s meaning in another, indifferent person – that seems like such a sadness! I cringe when this piece is discussed as some sort of hyper-romantic gesture. This isn’t love. That requires two real, flawed people. Kamila isn’t present in these pages – only Janáček’s picture of her. His fetishized, idealized woman. ————— And for me, that’s the catch, the entry point to this bizarre artwork, only briefly visible. When I think about enigmatic Kamila… then I think about men chasing women who don’t want them. And I don’t want to hear any more. But if I acknowledge that only one personality is truly enshrined in this music – Leoš Janáček himself, and all of his desires – then I can begin to accept it as sympathetic, flawed, and deeply moving. –David Rubin, CMW Fellow 2017-2019 Join us for one (or both!) of these performances: Saturday, March 3 at 7pm Sunday, March 4 at 3pm |