Debussy’s Unfinished Work

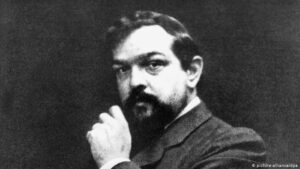

By Jeff Louie Claude Debussy’s sonata for violin and piano, written in 1916-1917, was the last significant composition he completed. Its premiere, on which he played the piano part himself, was his final public performance. The sonata was the third of what he had intended to be a six-sonata cycle, after the sonata for cello and piano from 1915 (performed a few years ago in the CMW Sonata Series by Zan Berry and Sakiko Mori) and the sonata for flute, viola and harp, also from 1915. Before these sonatas, Debussy had not written any type of chamber music in more than two decades, since his string quartet from 1893. (That string quartet is such a masterpiece that perhaps he felt he had nothing more to add to the chamber music repertoire?) Debussy is a profoundly significant figure in the history of western classical music. Yet he is broadly embraced and beloved in a way that similarly important composers of the era (e.g. Schoenberg or Stravinsky) often are not. Debussy’s willingness to discover the sounds of other cultures and to break the harmonic conventions of his own—the centuries-old rules about which notes were allowed to go together and how certain sound combinations were supposed to resolve—wasn’t merely about defiance; it was always about finding better and more original ways of evoking emotion through his art. His sensitivity to the feelings that sound combinations could hint at imbues his music with a uniquely visceral appeal. What happens to a rule-breaking artist once they’ve created their ground-breaking masterpieces—after they’ve broken all the rules? Where do you find inspiration after you’ve scorched the earth? There’s a bit of a pattern for many artists: they often pare down, shed the excesses, and look backwards. After the youthful “Russian phase” of Stravinsky’s career (which included the most incendiary, revolutionary works of his career, including Petroushka and The Rite of Spring), Stravinsky turned to baroque and early classical music for inspiration for his “neoclassical phase,” featuring sparser and more formally rigid music. (An example from another genre—after the extravagances of Sgt. Pepper and the White Album, the Beatles made a conscious effort to “Get Back” to their stripped-down rock and roll roots.) In Debussy’s case, he was drawn to the great French composers from the past, particularly Rameau and Couperin. The sonatas of Debussy’s late sonata cycle are not the sonata forms of Beethoven and Schubert, but resemble more closely the form of 18th century “monothematic” sonatas. In other words, don’t listen to them waiting for a distinctive second theme to come in establishing a new tonal center and then anticipate its triumphant restatement later in the home key! But, as in all Debussy, do listen to the subtle changes in texture, to the way a snippet of melody is repeated on top of a slightly altered accompaniment, and notice how these details make you feel—how a new harmony can add a dark undertone to a previously insouciant tune, how a small up-and-down gesture in the violin creates an ephemeral sniff of dread. Also, particularly in the violin sonata’s second movement, listen for the sense of mischief—Debussy had a great talent for incorporating playfulness into his music. Debussy’s plans for the other sonatas in the cycle included one for oboe, horn, and harpsichord, and one for trumpet, clarinet, bassoon, and piano. The sixth and final sonata was to combine all the instruments of all the other sonatas into a concerto grosso type of composition, focusing on all the different sonorities that combination of instruments could produce. Unfortunately he passed before he was able to complete this project. One can only wonder if, had he lived longer, his late-career return to small ensembles would have produced even more masterpieces to the chamber music repertoire. *** Jeffrey Louie is an accomplished instrumentalist, composer, and arranger across a wide range of musical disciplines. A virtuoso pianist and violinist, he has soloed on both instruments with numerous Boston-area orchestras and has served as principal second violinist for the Yale Symphony and the Boston Philharmonic. As a pianist in Providence, he is a frequent collaborator with Community MusicWorks and with faculty and students at Brown University. He is a BMI Student Composers Award winner, and at Yale received the Wrexham Prize in Music and the Abraham Beechman Cox Prize for music composition. Jeffrey is also a singer/songwriter and guitarist, as well as a versatile arranger and session musician for a diverse roster of ensembles and recording artists. An avid cruciverbalist, he recently had a crossword puzzle published in the Los Angeles Times. Hear Debussy’s work performed by Jeff Louie and Lisa Barksdale in our YouTube Sonata Series event. |