Writer, speaker, and social activist Arlene Goldbard talks with CMW’s Founder & Artistic Director Sebastian Ruth about how classical music can connect with community arts and cultural democracy on a new episode of her podcast, “A Culture of Possibility.”

Three ways to listen!

Dayana performs this past spring at a CMW event.

Dayana performs this past spring at a CMW event.  Dayana’s first trip to Los Angeles included a view of the famous Hollywood sign.

Dayana’s first trip to Los Angeles included a view of the famous Hollywood sign. Dayana, left, with new friend Mia at the YOLA summer program.

Dayana, left, with new friend Mia at the YOLA summer program.  Lightsabers abound at the Hollywood Bowl concert conducted by John Williams.

Lightsabers abound at the Hollywood Bowl concert conducted by John Williams. The YOLA National performs at the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

The YOLA National performs at the Walt Disney Concert Hall. Congratulations to Liam Hopkins (left) and AlexisMarie Nelson (right) on graduating in the first cohort of the Alumni Fellowship Program! AlexisMarie and Liam recently took time to reflect on their experiences at CMW over the past two years and shared them with us.

Congratulations to Liam Hopkins (left) and AlexisMarie Nelson (right) on graduating in the first cohort of the Alumni Fellowship Program! AlexisMarie and Liam recently took time to reflect on their experiences at CMW over the past two years and shared them with us.

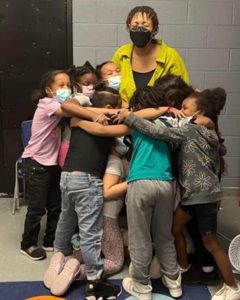

AlexisMarie receives well-deserved hugs from student in the Daily Orchestra Program.

AlexisMarie receives well-deserved hugs from student in the Daily Orchestra Program.

Liam rocks the bass with students at the End-of-Year Student Gala.

Liam rocks the bass with students at the End-of-Year Student Gala.