Cellist Lauren Latessa has spent her post-CMW Fellowship time creating The Music Project (and getting married: congratulations, Lauren and Ryan!). Recently, Lauren updated us on the project’s developments.

“This project saved my life. Suddenly I realized the arch of my life could go up again. I found something I loved and could give back to.” — a participating senior.

Hello CMW friends!

As many of you know, I have spent the last three years creating and developing a music program for a large retirement community in Rockville, MD. I am a full-time employee and feel very lucky to work with talented, thoughtful colleagues across the artistic spectrum. Each day I learn more about how to harness music’s power to provide joy, meaning, and texture to a time of life that is often filled with loneliness and isolation.

In this video, senior resident Marjorie talks about the impact that the Music Project has had in her life: “I think the only thing that keeps you alive is learning new things.”

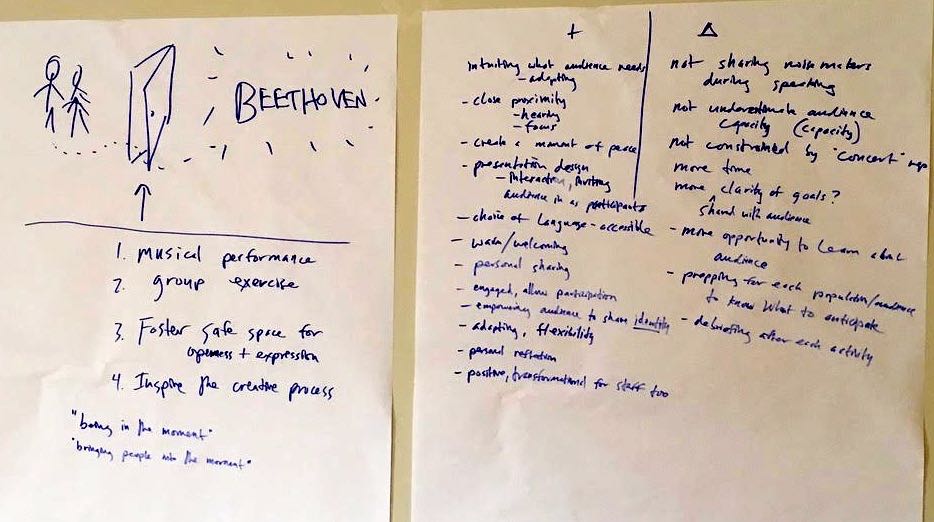

In February of 2017, this project took a huge step forward as I welcomed Sara Matayoshi and Jessica McKee and formed the Iris Piano Trio. Three days a week we collaborate with elders from four retirement communities, working in independent living, assisted living and memory care contexts. Each year we curate an annual rotation of concerts, open rehearsals, participatory group programs and one-on-one sessions designed specifically for these communities.

This past year has been an incredible journey, full of peaks and valleys as we’ve navigated our way through the different environments and found our voice as a trio. We are thrilled to now be embarking on our second year working at the intersection of creative placemaking and creative aging!

The trio is just putting together our website (www.irispianotrio.com) and newsletters. Send an email to contact@irispianotrio.com if you’d like to be added to our monthly newsletter!

Wishing you all the best in 2018,

Lauren Latessa

CMW Cello Fellow 2012-2014

Learn more about The Music Project’s day-to-day activities in this blog post.