Join us Thursday, November 16 at 7pm for our popular Sonata Series in the beautifully appointed Grand Gallery at RISD Museum. This concert features violinists Sebastian Ruth and David Rubin with guest pianist Eliko Akahori. Here, violinist David Rubin shares his notes on the piece he’ll perform at the event and his own process of discovery on the meaning and origin of Copland’s Sonata for Violin and Piano. Join us Thursday, November 16 at 7pm for our popular Sonata Series in the beautifully appointed Grand Gallery at RISD Museum. This concert features violinists Sebastian Ruth and David Rubin with guest pianist Eliko Akahori. Here, violinist David Rubin shares his notes on the piece he’ll perform at the event and his own process of discovery on the meaning and origin of Copland’s Sonata for Violin and Piano.

I heard about Aaron Copland’s Sonata for Violin and Piano years before I actually heard Aaron Copland’s Sonata for Violin and Piano. The initial encounter looms large in my memory and — come to think of it — stands in opposition to my current experience of the piece. Tension can often be generative, as we say at CMW, so perhaps this story will be of some interest for those folks planning to attend our Sonata Series performance at the RISD Museum (Thursday, November 16 at 7pm in the Grand Gallery).

***

In 2004, pianist Karl Paulnack gave a welcome address to the parents of incoming students at Boston Conservatory. Seeking to reassure a presumably anxious crowd about the viability of their children’s chosen career path (read: financial ruin?), Paulnack shared stories about music’s healing powers, its necessity in our society, and the potential nobility of a life spent in its service. One of those anecdotes centered around Paulnack’s own performance of – you guessed it – the Copland violin sonata. This story is better in Paulnack’s telling, but I’ll briefly summarize it here.

During this performance of the Copland (let’s set the stage, actually: during the elegiac slow movement, at a small-town nursing home) a World War II veteran in the audience was clearly overcome with emotion. Later in the concert, Paulnack shared more details about the piece, including the story of its dedication to Harry Dunham, a pilot killed in battle during World War II and a close friend of Copland’s. At this point, the veteran in the audience stood up and left. He later told Paulnack that he was in shock – Copland’s music had triggered a vivid remembrance of a near-identical experience from his own wartime service, a particular trauma he hadn’t thought of in years. The veteran wanted to know how this was possible. How could Copland’s music make him remember so vividly, even though he hadn’t known about that particular connection when he first listened to the piece?

Paulnack’s story is a beautiful testament to music’s communicative powers. It’s also some heavy interpretative baggage for a performer to assimilate. From then on, I remembered the Copland sonata as the World War II piece that, by virtue of its somber American-ness, went straight to the heart.

And I’m not alone. To quote a random YouTube commenter:

“Is this the one about the pilot shot down in WWII?”

***

Now, when I play this piece, I have more information to draw on, and it makes things more complicated for me as a performer. New perspectives nudge that simple origin story out of my head, or at least force it to share space. Here’s a taste of that stew.

The ink was dry – the piece was finished – when Copland learned of Lieutenant Harry H. Dunham’s death, at which point he added the dedication. We have no way of knowing what he was thinking about while he was writing the violin sonata. It is a wartime piece because it was written during the war, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that this is a piece about war, or a piece about Dunham. It’s entirely possible that Copland didn’t think about the war – or his friend – at all while he was committing these notes to paper.

We know only what (little) Copland chose to share about it, namely: “I had little desire to compose a dissonant or virtuosic work, or one that incorporated folk materials. Nevertheless, certain qualities of the American folk tune had become part of my natural style of composing, and they are echoed in the Sonata.” Nicely put, Aaron.

We also know that the premiere drew polarized responses from critics. One damned its “rearward vision” (ouch!), while another (Copland’s friend Virgil Thomson) praised its “calm elevation… irresistibly touching.” That’s more like it. Wouldn’t we all like to be praised for our “calm elevation?”

I also know what my teachers have shared about their experience with this piece, and what various smart people have written. My mentor in graduate school was fascinated by Copland’s habit of spreading common, everyday chords across wide spans on an instrument’s range (think of a pianist playing high and low notes at the same time) – the harmony might be utterly familiar, but its presentation is unearthly. It creates the illusion of space, of solitude… of frontiers. Stan Kleppinger, in the journal of the Society for Music Theory, suggests that this piece’s special sonorities can be explained as dualities, moments when two key areas exist simultaneously – the magic lies in the ambiguity. Other scholars hear past the melodic inflections in Copland’s writing (and the related, pesky question of American-ness, which seems to dominate all conversations of this composer’s music) toward a neoclassical reading, in which canons and miniature fugues dance in 20th-century dress. Bach in Hollywood in 1943.

***

And even though the dedication was added after the piece’s completion, I can’t help but also wonder about this man, this Harry Dunham. It turns out that we know a bit about him, too, largely thanks to the work of Copland-scholar Howard Pollack.

We know that Dunham was incredibly handsome (in composer David Diamond’s words: “the most adorable, good-looking boy”), the darling of a New York arts community that starred Copland, Virgil Thomson, Paul Bowles, John Latouche, and other familiar figures. We know that he came from money, that he graduated from Princeton, that he made films. We know he was, to some degree, a leftist. We know that he married a woman, Marian Chase, but we also know that he was romantically involved with several men in the artistic circles he moved in. We know that Dunham, Bowles, and Copland traveled together in Morocco. We know that he died in battle in 1943, and that Aaron Copland dedicated this stunning piece of music to his memory.

I wasn’t expecting Dunham’s story to be so rich. The anonymous “pilot” from my initial encounter with the Copland violin sonata has a lot in common with me, and with people I’ve known. His sexuality, his artistic and political leanings, his social circles – they all run contrary to the military stereotype that I conjured up upon first hearing. This speaks to my prejudices, but it also speaks to the simple fact that people are complicated. In fact, Dunham’s surprises form a nice parallel with the rich ironies of Copland’s own story. Copland, the man whose music was appropriated for “Beef! It’s What’s for Dinner!” or Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America!” was, in Alex Ross’ words, “a gay leftist of Russian-Jewish extraction.” The man who created an American identity in concert music wasn’t always particularly welcome in his own country. Chew on that for a moment. These are not new ironies, but they never cease to amaze.

***

So, in the end, what should a performer make of these accumulated, sometimes contradictory meanings and associations? Perhaps it’s a cop-out, but here’s an attempt. I’m not a historian and I’m not a theorist and I’m not a veteran, but I do know what this piece makes me feel. Now, as I type this, I think of the piece’s opening, and its particular magic: a series of plain-spoken piano chords; hanging in the air, unresolved, still. Just the thought of those chords makes me verklempt. They’re 100% Copland, and they just break your heart.

I imagine Copland’s dedication to Dunham as a monument to an individual life, yes, but also a way of life: a group of friends, and a particular moment in time and space. In the composer’s words:

“By reflecting the time in which one lives, the creative artist gives substance and meaning to life as we live it. Life seems so transitory! It is very attractive to set down some sort of permanent statement about the way we feel, so that when it’s all gone, people will be able to go to our art works to see what it was like to be alive in our time and place — twentieth-century America.”

I love that little word: our. You get the sense that Copland’s our was broad as can be. “Our” twentieth-century America was gay and Jewish and left, just as much as it was the opposite of those things.

***

For me, this is the fun of performing. You live inside of a piece, soak up its contradictions and cliches, and try to make sense of it – both the thing itself (whatever that means, God help us) – and your relationship to it. Each realization of a piece, each usage in a different context, is a fleeting act – but over time it forms a discourse, a discussion across decades. It’s a beautiful mess, but that’s where the meaning is. A generative tension.

In any case. I hope you’ll join Eliko, Sebastian and I for Thursday’s program at the RISD Museum. It’ll be a pleasure to explore this piece, in all of its contradictions. In so doing, I hope we’ll celebrate Aaron Copland’s life — Harry Dunham’s, too.

-David Rubin, Violin Fellow

Further reading & works quoted above

Howard Pollack, Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. Henry Holt, 1999.

Karl Paulnack, welcome address at The Boston Conservatory, 2004. Accessible here.

Alex Ross, The Rest is Noise. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Aaron Copland and Vivian Perlis, Copland Since 1943. St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Gail Levin and Judith Tick, Aaron Copland’s America. Watson-Guptill Publications, 2000.

Within the past twenty-one years, CMW has offered professional musicians opportunities to re-imagine the very foundations of a classical music career, and to think more broadly about music as a way of engaging in and with communities.

This year, CMW has the opportunity to deepen that work with the support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for a new initiative, Citizens of the World: Forging Pathways to College and Beyond. This strategic initiative is designed to substantially increase the number of racially diverse, low-income young people who gain access to critical skills that promote success. This work builds on CMW’s 20-year history of developing music-based education programs designed to open new worlds of opportunity to low-income African-American and Latino youth. Out of this work has come Phase II, an approach to developing fundamental skills and supports that promote college-going, that has led 95% of CMW graduates to continue to college.

CMW will share CMW’s successful college-going model across a network of community-based music education sites. Called the MusicWorks Network, this project will link 10-15 community-based music sites serving over 650 young people and convene them in an annual Summer Institute for training, resource-sharing, and collaborative evaluation.

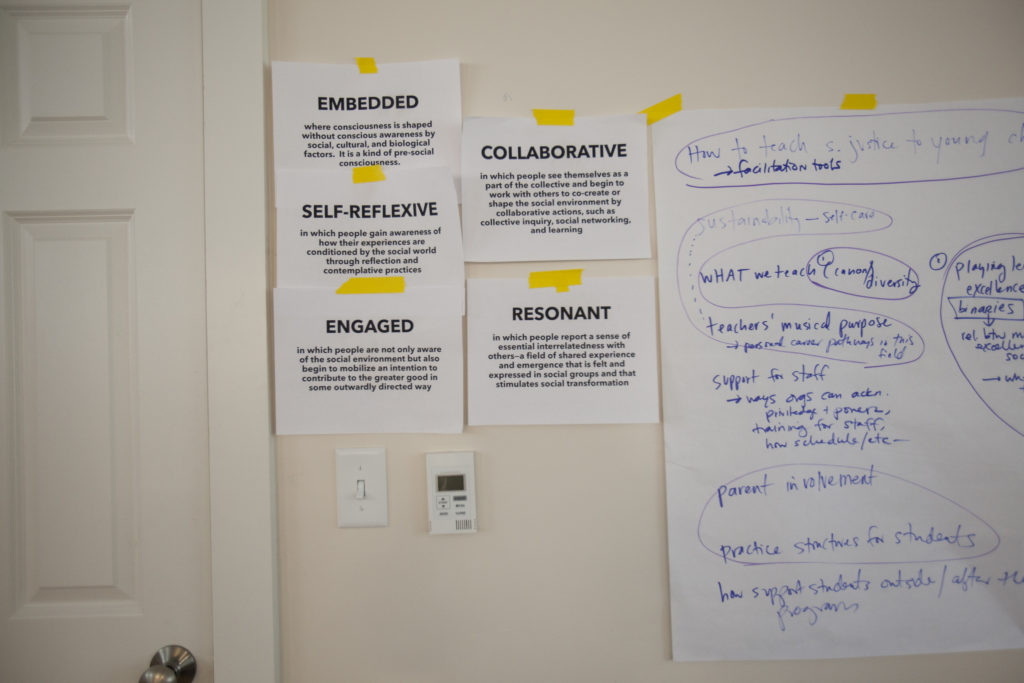

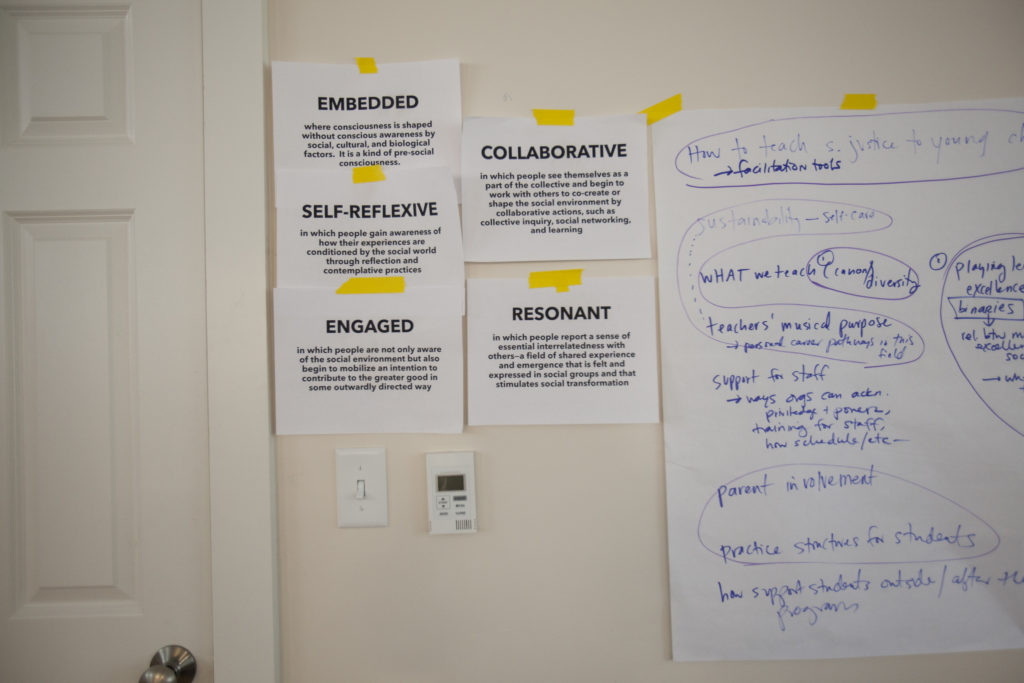

The first Summer Institute took place this past August 22-30 as educators and staff from ten different organizations gathered at the beautiful Rolling Ridge Conference Center in North Andover, MA. Connecting around the ways that social justice practices and technical and artistic work on string instruments can support one another, teachers and staff came from Community MusicWorks, MusiConnects (Boston, MA), MyCincinnati (Cincinnati, OH), Musica Franklin (Franklin, MA), Orchestra of St. Luke’s (New York, New York), MusicHaven (New Haven, CT), Newport Strings (Newport, RI), Sistema New Brunswick (New Brunswick, St. John, Canada), Strong Harbor Strings (St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada), and Neighborhood Strings (Worcester, MA).

Participants convened for a range of workshops and trainings, including a 2-day string pedagogy workshop with renowned violinist and teacher Mimi Zweig, a poetry and social justice workshop with poet Jonathan Mendoza, a workshop on anti-racist organizational frameworks with trainer and activist Adeola Oredola, and discussions and reflection around the creative synergy between string pedagogy and social justice teachings.

The Institute was designed and facilitated by Sebastian Ruth and Chloe Kline with the new MusicWorks Network staff: MusicWorks Network Director Jori Ketten and MusicWorks Network Fellow Andrew Oung. Part of the initiative, the MusicWorks Network Fellowship is a one-year position for alumni of CMW’s youth program or graduates of CMW’s two-year Fellowship Program to contribute to the MusicWorks Network. Andrew is our first alumni hire at CMW.

On Our Way: Welcome to Season 21!

This year, Community MusicWorks launches its third decade, and as we step into the next chapter of this organization’s growth our work is urgent in new ways. Twenty years ago the idea of a string quartet in a permanent residency in an urban neighborhood was a fringe idea in classical music. The notion that an urban residency would be the core of a chamber group’s life and work and that community development would be an equal ambition to playing and teaching was new territory.

Now, two decades in, conservatories are graduating students with entrepreneurship training, many with a social change focus; musicians are seeking alternate venues to the traditional concert halls, and increasingly orchestras and concert series are investing in their communities. All this points to a movement that is robust, respected, and ever growing: musicians experimenting with new forms, new career paths, and new inquiries into the place of musicianship in contemporary life.

CMW in our third decade has a new task to help grow this generation of students and musicians. With the launch of our MusicWorks Network and Fellowship, supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, we lead a new conversation across the country into the connections between social justice and musical practice, and share ways in which young people’s participation in programs like CMW can support their paths to and through college. We are thrilled to be bringing together former participants from both the CMW Fellowship Program and Institutes for Musicianship and Public Service, now leading programs of their own in more than 15 cities across the country and in Canada, to grow and learn together.

In our concert series, Season 21 offers adventurous programming. You’ll notice that most programs feature one or more female composers’ works, an intentional effort to align our concert programming with our commitment to equity and social justice. From the season opener to the June finale, you’ll be invited into new sonic experiences—the driving intensity of Julia Wolfe’s “Cruel Sister,” a new work by Annika Socolofsky, a festival celebrating André Cormier’s quiet masterpieces, and the premiere of a work by Rhode Island composer Forrest Larson. There are many opportunities for new sounds and experiences!

Our tradition of Bach in November continues, including the fifth year of the overnight Bach marathon. This season also features a special benefit performance by Johnny Gandelsman (of Brooklyn Rider and the Silk Road Project) of all the Bach solo works for violin—a spiritual and physical feat rarely undertaken, even by violinists of the greatest stamina.

Our December Solstice Concert returns—back by popular demand! The storytelling and musical adventure takes us again from foxes and crows to the wind and a chickadee, whose song reminds us that music can bring light and hope—a wonderful allegorical tale that reflects CMW’s mission.

One final thought to carry with you as you help launch this third decade—our work is about each person’s continual development, or what Maxine Greene would call “being on the way.” From our students to our musician-teachers, to audience members and supporters, CMW’s mission focuses on encouraging all of us to be continually on our way—toward growth, deeper awareness, and indeed transformative experiences of beauty and community.

Let’s step together into the work of this third decade!

-Sebastian Ruth, Founder & Artistic Director

Check our Season 21 calendar here.

This year Community MusicWorks turns 20! To mark the milestone, we are gathering the stories of 20 members of our community–musicians, students, parents, graduates and supporters. Look for new stories throughout the season.

Interviews were recorded, transcribed and edited to create personal narratives in each subject’s distinctive voice. We hope 20 Years, 20 Stories captures the many flavors and varieties of CMW experience. Join us at a concert anytime to start creating your own CMW story.

Read the interviews here.

I am honored to be a part of the US Department of Arts and Culture, an organization that in all its work practices the practice of social imagination–imagining the world as it could be otherwise.

As the “Secretary of Music and Society” on the U.S. Department of Arts and Cultural National Cabinet, I’m delighted to help launch #RevolutionOfValues, a day of creative action on April 4th, 2017, the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, powerful speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” This is the most-quoted part of the Riverside Speech:

[W]e as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a “thing-oriented” society to a “person-oriented” society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

Fifty years later, to walk in his footsteps, to give voice once again to his powerful words, and to kick off a year of efforts by many organizations around the U.S. to remind people of Dr. King’s real message and unfinished work, the USDAC and partners are sponsoring #RevolutionOfValues. Any individual or organization can take part by hosting an event and/or sharing images or texts via social media inspired by Dr. King’s historic speech. Detailed instructions and resources are available in the free #RevolutionOfValues Toolkit. Download here and join us!

–Sebastian Ruth

Founder & Artistic Director

“This is really a lifelong investment in people. In their musicianship and their humanity, and certainly I would hope that that feedback loop continues to deepen, so that some of our graduates will be running the organization sometime down the road.”

Rhode Island Public Radio’s recent piece on Community MusicWorks’ 20th season features a conversation with CMW’s Sebastian Ruth.

Listen here.

I am honored to be a part of the US Department of Arts and Culture, an organization that in all its work practices the practice of social imagination–imagining the world as it could be otherwise.

As the “Secretary of Music and Society” on the U.S. Department of Arts and Cultural National Cabinet, I’m delighted to help launch #RevolutionOfValues, a day of creative action on April 4th, 2017, the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, powerful speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” This is the most-quoted part of the Riverside Speech:

[W]e as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a “thing-oriented” society to a “person-oriented” society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

Fifty years later, to walk in his footsteps, to give voice once again to his powerful words, and to kick off a year of efforts by many organizations around the U.S. to remind people of Dr. King’s real message and unfinished work, the USDAC and partners are sponsoring #RevolutionOfValues. Any individual or organization can take part by hosting an event and/or sharing images or texts via social media inspired by Dr. King’s historic speech. Detailed instructions and resources are available in the free #RevolutionOfValues Toolkit. Download here and join us!

-Sebastian Ruth

Founder & Artistic Director

As CMW musicians have been working over the past several weeks to articulate our response as artists and citizens to the many events of the new administration, our discussions have toggled between the actions we need to take raising our voices as engaged citizens and making music.

New Yorker music critic Alex Ross, who once profiled CMW, takes on this question in his post about how musicians make music in a time of rage. Ross quotes Lucy Caplan*, whose essay about CMW’s 2016 Art and Social Action symposium is The World You Want to Live In: New Paradigms for the Arts.

*A fun fact: Lucy worked with CMW’s Sebastian Ruth as a student in his Yale class, and then as a TA in his Music and Social Action Coursera class. Read more about Lucy here and here.

Links:

Alex Ross: Making Art in a Time of Rage

Alex Ross: Learning the Score (CMW Profile in the New Yorker)

Lucy Caplan: The World You Want to Live In: New Paradigms for the Arts

Sebastian Ruth: Music and Social Action (Coursera)

Linda Daniels is a writer, editor, cellist, CMW parent, former CMW Board member and expert eavesdropper. She helms the 20 Years, 20 Stories project and this is her story.

I’ve been an eavesdropper since childhood. My mother liked to pour herself a Royal Crown cola in the late afternoon, park herself on the couch and telephone her mother, which was my cue to c-a-r-e-f-u-l-l-y raise the extension handset upstairs. Usually, they discussed mundane matters: pork chops versus chicken, how this season’s fashions were so unflattering and, now and then, family gossip. The topics were almost beside the point, except for the family gossip, which is why I eavesdropped in the first place. But I was also intrigued by the mysterious current of poetry running beneath even the most routine remarks. I loved the give and take of conversation, the sighs and pauses, the sound of my mother’s sympathetic tsk-tsk’s and my grandmother’s pretty brogue. I almost always got busted and was scolded, but not seriously enough to deter me from future attempts. Talking was as close as my family got to making music. No one sang or played an instrument, and my relatives just embarrassed themselves trying to clap along to music, but man, could these people talk. Listeners, even illicit ones, had a role to play, too. We completed the performance circle.

In college, Studs Terkel’s oral history Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do shaped my senior year thesis. I made the leap from habitual eavesdropper to scholarly interviewer and collected the oral histories of women who came of age during the 1920s. The best parts of the resulting 200-plus-page door-stopper were their reminiscences. After college, I became a reporter: more listening, more writing. Even after I quit newspapers and turned to other pursuits, I never lost the eavesdropping habit. My husband recognizes the faraway look that crosses my face when we’re in a public space and I hear something that bears further investigation, convinced, of course, that no one can tell what I’m up to. After 27 years, he also knows that whatever he and I were talking about will have to wait. More recently, I’ve been inspired by writer Svetlana Alexievich, who won a Nobel for Secondhand Time, her beautifully rendered oral history of post-Soviet Russians.

In September, I began an exciting new listening and writing project in connection with Community MusicWorks’ 20th anniversary: collecting 20 representative stories of CMW musicians, staff, students, parents and supporters. I’ve been expertly assisted by CMW fellow Josie Davis, who interviewed three people, and Communications Manager Liz Cox, who proofreads the stories and designs the online content. (Read the stories here.)

It hasn’t been difficult to get people to open up. I’ve been a familiar face at CMW since my youngest had his first cello lesson here ten years ago. I’ve exchanged knowing glances with other parents when a beginner nails “Twinkle” and held a collective breath during the dying notes of a Beethoven quartet performed by the pros. I’ve square-danced to fiddle tunes and attempted, much less successfully, the salsa. I’ve sung rounds and set up folding chairs; fretted over budgets and strategic goals; eased my car past side-view mirrors on snow-bound Messer Street; knitted for newborns; and eaten far too much pizza.

Since people know me better as an at-large mom than as an interviewer and writer, some of my questions may discomfit. Recently, a student I was interviewing put up a hand and blurted, “That’s a weird question!” Um, ok. But can you answer it anyway? I remain confident that what I’m curious about others are too. She answered in good faith, trusting that I have her back. I am honored by that trust. You readers should be also. When people talk honestly they make themselves vulnerable. They don’t want to be misconstrued as they describe emotions and realizations that can’t be summarized by facts alone. This is especially true of CMW’s staff, who are talking about their life’s work.

It’s why I take the final step of the oral history process so seriously: converting 8-20 pages of interview transcript to a narrative that honors the speaker’s intentions, captures history while it’s still occurring, and compels readers. It’s a messy process. No matter how cleverly I order the questions and pursue answers during an interview, the talk meanders, as talk will. Even the most prepared and polished speakers wander off topic and speak colloquially, thank goodness. They are thinking out loud, which is where the music happens. It’s the difference between watching an official read a prepared statement from behind a podium and hearing him speak spontaneously from the heart when a reporter surprises him off-stage by asking exactly the right question at the right moment. I’m going for the latter.

Some “20 Years, 20 Stories” subjects have been flummoxed by the difference between the hour-plus interview they remember and the 2-5 page story I produce, having edited and condensed our conversation to a fare-thee-well, absenting my questions along the way. (Available here, if you’re curious.) They worry about being misperceived and about sounding too casual. They worry that they have said too much or too little. It is scary to see your constantly morphing thoughts marching in regimental black lines across white space. Where are the raised eyebrows signaling sincerity or the smile signaling warmth? Where are the tears that welled up when recalling a triumphant moment with a challenging student? Where’s a second or third chance to rephrase? To be more thoughtful? To explain more fully?

Oral history and chamber music have much in common. Both art forms strive to capture human experience through artifice and collaborative effort, and both are very much of the moment. Therein lies the thrill. Having made the artistic decision to omit interview questions in favor of narrative flow, I don’t worry that readers need cue cards. I trust that readers will appreciate what I appreciate about oral history: the idiosyncratic quirks of everyday speech as thoughtful people talk about things that matter. Subjects can trust their beautiful, one-of-a-kind voices to tell the story. The rest of us can pick up the extension and listen in.

The 20 Years, 20 Stories homepage.

Last week during All Play Day, students participated in a masterclass with special guests: renowned violinist James Buswell, violinist Ealain McMullin (a former CMW fellow and co-director of The Newport String Project), cellist Carol Ou, and violist Jason Amos (former CMW Fellow and member of the Boston Public Quartet). A masterclass is an opportunity for students to receive feedback on their playing in front of peers. It is a great learning experience for performers and audience-members to watch a teacher in action, ask questions, and explore musical ideas together.

It has been particularly rewarding to follow up with students this week about what they learned from the class. My violin student Ella remarked “I learned that it’s important to warm-up with scales. I liked hearing him [Mr. Buswell] play for us.” Some students are already incorporating new ideas into their playing. It was a great afternoon of sharing and learning and we are grateful to the teachers for joining us at All Play!

–Josie Davis, Violin Fellow

|

|

Join us Thursday, November 16 at 7pm for our popular Sonata Series in the beautifully appointed Grand Gallery at RISD Museum. This concert features violinists Sebastian Ruth and David Rubin with guest pianist Eliko Akahori. Here, violinist David Rubin shares his notes on the piece he’ll perform at the event and his own process of discovery on the meaning and origin of Copland’s Sonata for Violin and Piano.

Join us Thursday, November 16 at 7pm for our popular Sonata Series in the beautifully appointed Grand Gallery at RISD Museum. This concert features violinists Sebastian Ruth and David Rubin with guest pianist Eliko Akahori. Here, violinist David Rubin shares his notes on the piece he’ll perform at the event and his own process of discovery on the meaning and origin of Copland’s Sonata for Violin and Piano.